This spring brings new imaginings of John Carter of Mars both on film and in print. Please enjoy this exclusive excerpt from Under The Moons of Mars, a new anthology of John Carter stories edited by John Joseph Adams, out on February 7th from Simon & Schuster.

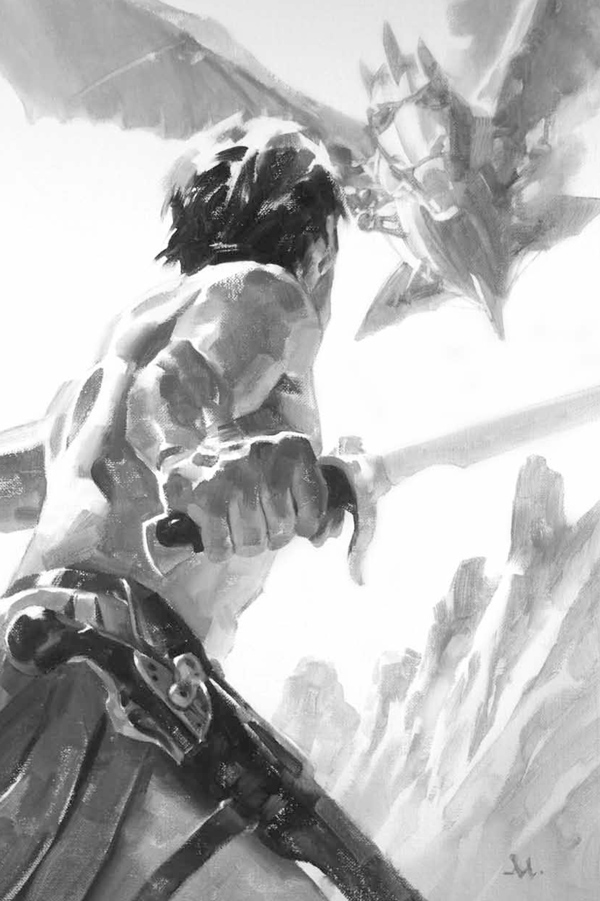

Find out more about this story and the anthology in John’s introduction, or visit the promotional site for more information. You can also see how Gregory Manchess’ art for this story was created.

I suppose some will think it unusual that mere boredom might lead a person on a quest where one’s life can become at stake, but I am the sort of individual who prefers the sound of combat and the sight of blood to the peace of Helium’s court and the finery of its decorations. Perhaps this is not something to be proud of, but it is in fact my nature, and I honestly admit it.

Certainly, as Jeddak of Helium, I have responsibilities at the court, but there are times when even my beloved and incomparable Dejah Thoris can sympathize with my restlessness, as she has been raised in a warrior culture and has been known to wield a sword herself. She knows when she needs to encourage me to venture forth and find adventure, lest my restlessness and boredom become like some kind of household plague.

Of course, she realizes I may be putting my life on the line, but then again, that is my nature. I am a fighting man. I find that from time to time I must seek out places where adventure still exists, and then, confronted by peril, I take my sword in hand. Of course, there are no guarantees of adventure, and even an adventurous journey may not involve swordplay, but on Barsoom it can be as readily anticipated as one might expect the regular rising and setting of the sun.

Such was the situation as I reclined on our bedroom couch and tried to look interested in what I was seeing out the open window, which was a flat blue, cloudless sky.

Dejah Thoris smiled at me, and that smile was almost enough to destroy my wanderlust, but not quite. She is beyond gorgeous; a raven-haired, red-skinned beauty whose perfectly oval face could belong to a goddess. Her lack of clothing, which is the Martian custom, seems as natural as the heat of the sun. For that matter, there are no clothes or ornaments that can enhance her shape. You can not improve perfection.

“Are you bored, my love?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I am fine.”

“You are not,” she said, and her lips became pouty. “You should know better than to lie to me.”

I came to my feet, took hold of her, and pulled her to me and kissed her. “Of course. No one knows me better. Forgive me.”

She studied me for a moment, kissed me and said, “For you to be better company, my prince, I suggest you put on your sword harness and take leave of the palace for a while. I will not take it personally. I know your nature. But I will expect you to come back sound and whole.”

I hesitated, started to say that I was fine and secure where I was, that I didn’t need to leave, to run about in search of adventure. That she was all I needed. But I knew it was useless. She knew me. And I knew myself.

She touched my chest with her hand.

“Just don’t be gone too long,” she said.

I arranged for a small two-seater flyer. Dressed in my weapons harness, which held a long needle sword that is common to Barsoom, as well as a slim dagger, I prepared for departure. Into the flyer I loaded a bit of provisions, including sleeping silks for long Martian nights. I kissed my love good-bye, and climbed on board the moored flyer as it floated outside the balcony where Dejah Thoris and I resided.

Dejah Thoris stood watching as I slipped into the seat at the controls of the flyer, and then smiling and waving to me as if I were about to depart for nothing more than a day’s picnic, she turned and went down the stairs and into our quarters. Had she shown me one tear, I would have climbed out of the flyer and canceled my plans immediately. But since she had not, I loosed the mooring ropes from where the craft was docked to the balcony, and allowed it to float upward. Then I took to the controls and directed the ship toward the great Martian desert.

Soon I was flying over it, looking down at the yellow mosslike vegetation that runs on for miles. I had no real direction in mind, and decided to veer slightly to the east. Then I gave the flyer its full throttle and hoped something new and interesting lay before me.

I suppose I had been out from Helium for a Martian two weeks or so, and though I had been engaged in a few interesting activities, I hesitate to call any of them adventures. I had spent nights with the craft moored in the air, an anchor dropped to hold it to the ground, while it floated above like a magic carpet; it was a sensation I never failed to enjoy and marvel at. For mooring, I would try to pick a spot where the ground was low and I could be concealed to some degree by hills or desert valley walls. The flyer could be drawn to the ground, but this method of floating a hundred feet in the air, held fast to the ground by the anchor rope, was quite satisfying. The craft was small, but there was a sleeping cubicle, open to the sky. I removed my weapon harness, laid it beside me, and crawled under my sleeping silks and stretched out to sleep.

After two weeks my plan to find adventure had worn thin, and I was set to start back toward Helium and Dejah Thoris on the morning. As I closed my eyes, I thought of her, and was forming her features in my mind, when my flying craft was struck by a terrific impact.

The blow shook me out of my silks, and the next moment I was dangling in the air, clutching at whatever I could grab, as the flyer tilted on its side and began to gradually turn toward the ground. As I clung, the vessel flipped upside down, and I could hear a hissing sound that told me the flyer had lost its peculiar fuel and was about to crash to the desert with me under it.

The Martian atmosphere gave my Earthly muscles a strength not given to those born on the red planet, and it allowed me to swing my body far and free, as the flyer—now falling rapidly—crashed toward the sward. Still, it was a close call, and I was able to swing out from under the flyer only instants before it smashed the ground. As I tumbled along the desert soil beneath the two Martian moons, I glimpsed the flying machine cracking into a half dozen pieces, tossing debris—including my weapon harness—onto the mossy landscape.

Glancing upward, I saw that the author of the flyer’s destruction had turned its attention toward me. It was a great golden bird, unlike anything I had ever seen. It was four times the size of my flyer. As I got a better look, its resemblance to a bird evaporated. It looked more like a huge winged dragon, its coating of scales glinting gold in the moonlight. From its tooth-filled mouth, and easing out from under its scales, came the hiss of steam. With a sound akin to that of a creaking door, it dove at top speed toward me.

* * *

I practically galloped like a horse toward my weapon harness, and had just laid my hands on it and withdrawn my sword, when I glanced up and saw what I first thought was my reflection in the golden dragon’s great black eyes.

But what I saw was not my reflection, but the moonlit silhouettes of figures behind those massive dark eyes. They were mere shapes, like shadows, and I realized in that moment that the golden dragon was not a creature at all: It was a flying machine, something I should have realized immediately as it had not flapped its wings once, but had been moving rapidly about the sky without any obvious means of locomotion.

It dove, and as it came toward me, I instinctively slashed at one of its massive black eyes. I had the satisfaction of hearing it crack just before I dropped to my belly on the sward, and I felt the air from the contraption as it passed above me like an ominous storm cloud, perhaps as close as six inches.

It doesn’t suit me to lie facedown with a mouth full of dirt, as it hurts my pride. I sprang to my feet and wheeled to see that the flying machine was still low to the ground, cruising slowly, puffing steam from under its metal scales. I leapt at it, and the Martian gravity gave my Earthly muscles tremendous spring; it was almost like flying. I grabbed at the dragon’s tail, which was in fact, a kind of rudder, and clung to it as it rose higher and wheeled, no doubt with an intent to turn back and find me.

I grinned as I imagined their surprise at my disappearance. I hugged the tail rudder with both arms without dropping my sword, and pulled. The dragon wobbled. I yanked at it, and a piece of the tail rudder came loose with a groan. I fell backward and hit the ground with tremendous impact; I wasn’t that high up, but still, it was quite a fall.

As I lay on the ground, trying to regain the air that had been knocked out of me, I saw the craft was veering wildly. It smacked the ground and threw up chunks of desert, then skidded, bounced skyward again, then came back down, nose first. It struck with tremendous impact. There was a rending sound, like a pot and pan salesman tumbling downhill with his wares, and then the dragon flipped nose over tail and slammed against the desert and came apart in an explosion of white steam and flying metal scales and clockwork innards.

Out of anger and pure chance, I had wrecked the great flying machine.

Crawling out of the debris were two of the most peculiar men I had ever seen. They, like the dragon, were golden in color and scaled. White vapor hissed from beneath their metallic scales, and from between their teeth and out of their nostrils. They were moving about on their knees, clanking like knights in armor, their swords dragging in their harnesses across the ground.

Gradually, one of them rose to his feet and looked in my direction; his face was a shiny shield of gold with a broad, unmoving mouth and a long nose that looked like a small piece of folded gold paper. Steam continued to hiss out of his face and from beneath his scales.

The other one crawled a few feet, rolled over on his back, and moved his legs and arms like a turtle turned onto its shell . . . and then ceased to move at all.

The one standing drew his sword, a heavy-looking thing, and with a burst of steam from his mouth and nose, came running in my direction. When confronted by an enemy with a sword, I do not allow myself to become overconfident. Anything can go wrong at anytime with anyone. But for the most part, when a warrior draws his sword to engage me, I can count on the fact that I will be the better duelist; this is not brag, this is the voice of experience. Not only am I a skilled swordsman, but I have tremendously enhanced agility and strength on my side, all of it due to my Earthly muscles combined with the lighter Martian gravity.

On the armored warrior came, and within an instant we crossed swords. We flicked blades about, wove patterns that we were each able to parry or avoid. But now I understood his method. He was good, but I brought my unique speed and agility into play. An instant later, I was easily outdueling him, but even though my thin blade crisscrossed his armor, leaving scratch marks, I couldn’t penetrate it. My opponent’s armor was hard and light and durable. No matter what my skill, no matter how much of an advantage I had due to my Earthly muscles, eventually, if I couldn’t wound him, he would tire me out.

He lunged and I ducked and put my shoulder into him as I rose up and knocked him back with such force that he hit on his head and flipped over backward. I was on him then, but he surprised me by rolling and coming to his feet, swinging his weapon. I parried his strike close to the hilt of my weapon, drew my short blade with my free hand at the same time, stepped in and stuck it into the eye slot in his helmet.

It was a quick lunge and a withdrawal. He stumbled back, and steam wheezed out of the eye slot and even more furiously from out of his mouth and nose, as well as from beneath his armor’s scales. He wobbled and fell to the ground with a clatter.

No sooner had I delighted in my conquest than I realized there had been others in the wreckage, concealed, and I had made the amateur mistake of assuming there had been only two. They had obviously been trapped in the wreckage, and had freed themselves while I was preoccupied. I sensed them behind me and turned. Two were right on top of me and two more were crawling from the remains of the craft. I had only a quick glimpse, for the next thing I knew a sword hilt struck me on the forehead and I took a long leap into blackness.

I do not know how long I was out, but it was still night when I awoke. I was being carried on a piece of the flying dragon wreckage, a large scale. I was bound to it by stout rope and my weapon harness was gone. I did not open my eyes completely, but kept them hooded, and glancing toward my feet, saw that one of the armored men was walking before me, his arms held behind his back, clutching the wreckage I was strapped to as he walked. His scales breathed steam as he walked. It was easy to conclude another bearer was at my head, supporting that end, and I was being borne slowly across the Martian desert.

After a moment, I discarded all pretenses and opened my eyes fully to see that the other two were walking nearby. The fact they had not killed me when they had the chance, especially after I had been responsible for killing two of their own and destroying their craft, meant they had other ideas for me; I doubted they were pleasant.

The moonlight was bright enough that I could see that the landscape had changed, and that we were slowly and gradually descending into a valley. The foliage that grew on either side of the trail we were using was unlike any I had seen on Mars, though even in the moonlight, there was much I could not determine. But it was tall foliage for Mars, and some of it bore berries and fruit. I had the impression the growth was of many colors, though at night this was merely a guess made according to variation in shading.

Down we went, my captors jarring me along. I felt considerably low, not only due to my situation, but because I had allowed myself to fall into it. I might have defended myself adequately with my sword, but I had been so engaged with the one warrior, I had not expected the others. I thought of Dejah Thoris, and wondered if I would ever see her again. Then that thought passed. I would have it no other way. All that mattered was I was alive. As long as I was alive, there was hope.

“I still live,” I said to the heavens, and it startled my wardens enough that they stumbled, nearly dropping me.

We traveled like this for days, and the only time I was released was to be watered and fed some unidentifiable gruel and to make my toilet. Unarmed or not, I might have made a good fight had the blow to my head not been so severe. Fact was, I welcomed the moment when I was tied down again and carried. Standing up for too long made me dizzy and my head felt as if a herd of thoats were riding at full gallop across it.

I will dispense with the details of the days it took us to arrive at our destination, but to sum it up, we kept slowly descending into the valley, and as we did the vegetation became thicker and more unique.

During the day we camped, and began our travels just before night. I never saw my captors lie down and sleep, but as morning came they would check to make sure I was well secured. Then they would sit near the scale on which I was bound, and rest, though I never thought of them as tired in the normal manner, but more worn-down as if they were short on fuel. For that matter, I never saw them eat or drink water. After several hours, they seemed to have built up the steam that was inside their armor, for it began to puff more vigorously, and the steam itself became white as snowfall. I tried speaking to them a few times, but it was useless. I might as well have been speaking to a Yankee politician for all the attention they paid.

After a few days, the valley changed. There was a great overhang of rock, and beneath the overhang were shadows so thick you could have shaved chunks out of them with a sword. Into the shadows we went. My captors, with their catlike vision, or batlike radar, were easily capable of traversing the path that was unseen to me. Even time didn’t allow my eyes to adjust. I could hear their armored feet on the trail, the hiss of steam that came from their bodies. I could feel the warmth of that steam in the air. I could tell that the trail was slanting, but as for sight, there was only darkness.

It seemed that we went like that for days, but there was no way to measure or even estimate time. Finally the shadows softened and we were inside a cavern that linked to other caverns, like vast rooms in the house of a god. It was lit up by illumination that came from a yellow moss that grew along the walls and coated the high rocky ceilings from which dangled stalactites. The light was soft and constant; a golden mist.

If that wasn’t surprising enough, there was running water; something as rare on Mars as common sense is to all the creatures of the universe. It ran in creeks throughout the cavern and there was thick brush near the water and short, twisted, but vibrant trees flushed with green leaves. It was evident that the moss not only provided a kind of light, but other essentials to life, same as the sun. There was a cool wind lightly blowing and the leaves on the trees shook gently and made a sound like someone walking on crumpled paper.

Eventually, we came to our destination, and when we did I was lifted upright, like an insect pinned to a board, and carried that way by the two warriors gripping the back of the scale. The others followed. Then I saw something that made my eyes nearly pop from my head.

It was a city of rising gold spires and clockwork machines that caused ramps to run from one building to another. The ramps moved and switched to new locations with amazing timing; it all came about with clicking and clucking sounds of metal snapping together, unseen machinery winding and twisting and puffing out steam through all manner of shafts and man-made crevices. There were wagons on the ramps, puffing vapor, running by means of silent motors, gliding on smooth rolling wheels. There were armored warriors walking across the ramps, blowing white fog from their faces and from beneath their scales like teakettles about to boil. The wind I felt was made by enormous fans supported on pedestals.

The buildings and their spires rose up high, but not to the roof of the caverns, which I now realized were higher than I first thought. There were vast windows at the tops of the buildings; they were colored blue and yellow, orange and white, and gave the impression of not being made of glass, but of some transparent stone.

Dragon crafts, large and small, flittered about in the heights. It was a kind of fairy-tale place; a vast contrast from the desert world above.

The most spectacular construction was a compound, gold in color, tall and vast, surrounded by high walls and with higher spires inside. The gold gates that led into the compound were spread wide on either side. Steam rose out of the construction, giving it the appearance of something smoldering and soon to be on fire. Before the vast gates was a wide moat of water. The water was dark as sewage, and little crystalline things shaped like fish swam in it and rose up from time to time to show long, brown teeth.

A drawbridge lowered with a mild squeak, like a sleepy mouse having a bad dream. As it lowered, steam came from the gear work and filled the air to such an extent that I coughed. They carried me across the drawbridge and into the inner workings of the citadel, out of the fairy tale and into a house of horrors.

* * *

For a moment we were on streets of gold stone. Then we veered left and came to a dark mouthlike opening in the ground. Steam gasped loudly from the opening, like an old man choking on cigar smoke. There was a ramp that descended into the gap, and my bearers carried me down it. The light in the hole was not bright. There was no glowing moss. Small lamps hung in spots along the wall and emitted heavy orange flames that provided little illumination; the light wrestled with the cotton-thick steam and neither was a clear winner.

In considerable contrast to above, with its near-silent clockwork and slight hissing, it was loud in the hole. There was banging and booming and screaming that made the hair on the back of my neck prick.

As we terminated the ramp and came to walk on firm ground, the sounds grew louder. We passed Red Martians, men and women, strapped to machines that were slowly stripping their flesh off in long, bloody bands. Other machines screwed the tops of their heads off like jar lids. This was followed by clawed devices that dipped into the skull cavity and snapped out the brain and dunked it into an oily blue liquid in a vat. Inside the vat the liquid spun about in fast whirls. The brains came apart like old cabbages left too long in the ground. More machines groaned and hissed and clawed and yanked the victim’s bones loose. Viscera was removed. All of this was accompanied by the screams of the dying. When the sufferers were harvested of their bodily parts, a conveyer brought fresh meat along; Red Martians struggling in their straps, gliding inevitably toward their fate. And all the time, below them were the armored warriors, their steam-puffing faces lifted upward, holding long rods to assist the conveyer that was bringing the sufferers along, dangling above the metal men like ripe fruit ready for the picking.

* * *

The cage where they put me was deep in the bowels of the caverns, below the machines. There were a large number of cages, and they were filled mostly with Red Martians, though there were also a few fifteen-foot-tall, four-armed, green-skinned Tharks, their boarlike tusks wet and shiny.

The armored warriors opened a cage, and the two gold warriors, who had followed my bearers, sprang forward and shoved those who tried to escape back inside. I was unbound and pushed in to join them. They slammed the barred gate and locked it with a key. Men and women in the cage grabbed at the bars and tried uselessly to pull them loose. They yelled foul epithets at our captors.

I wandered to the far side of our prison, which was a solid wall, and slid down to sit with my back to it. Though I was weak, and in pain, I tried to observe my circumstances, attempted to formulate a plan of escape.

One Red man came forward and stood over me. He said, “John Carter, Jeddak of Helium.”

I looked up in surprise. “You know me?”

“I do, for I was once a soldier of Helium. My name is Farr Larvis.”

I managed to stand, wobbling only slightly. I reached out and clasped his shoulder. “I regret I didn’t recognize you, but I know your name. You are well respected in Helium.”

“Was respected,” he said.

“We wondered what happened to your patrol,” I said. “We searched for days.”

Farr Larvis was a name well-known in Helium: a general of some renown who had fought well for our great city. During one of our many conflicts with the Green Men of Mars, he and a clutch of warriors had been sent to protect citizens on the outskirts of the city from Thark invaders. The invaders had been driven back, Farr Larvis and his men pursuing on their thoats. After that, they had not been heard of again. Search parties were sent out, and for weeks they were sought, without so much as a trace.

“We chased the Tharks,” Farr Larvis said, “and finally met them in final combat. We lost many men, but in the end prevailed. Those of us who remained prepared to return to Helium. But one night we made our camp and the gold ones came in their great winged beasts. They came to us silently and dropped nets, and before we could put up a fight, hoisted us up inside the bellies of their beasts. We were brought here. I regret to inform you, John Carter, that of my soldiers, I and two others are all that remain. The rest have become one with the machine.”

He pointed the survivors out to me in the crowd.

I clasped his shoulder again. “I know you fought well. I am weak. I must sit.”

We both sat and talked while the other Red Martians wandered about the cell, some moaning and crying, others merely standing like cattle waiting their turn in the slaughterhouse line. Farr Larvis’s two soldiers sat against the bars, not moving, waiting. If they were frightened, it didn’t show in their eyes.

“The gold men, they are not men at all,” Farr Larvis told me.

“Machines?” I said.

“You would think, but no. They are neither man nor machine, but both. They are made up of body parts and cogs and wheels and puffs of steam. And most importantly, the very spirits of the living. Odar Rukk is responsible.”

“And who and what is he?” I asked.

“His ancestors are from the far north, the rare area where there is ice and snow. They were a wicked race, according to Odar Rukk, fueled by the needs of the flesh. They were warlike, destroying every tribe within their range.”

“Odar Rukk told you this personally?”

“He speaks to us all,” said Farr Larvis. “There are constant messages spilled out over speakers. They tell his history, they tell his plans. They explain our fate, and how we are supposed to accept it. According to him, in one night there came a great melting in the north, and the snow and much of the ice collapsed. Their race was lost, except for those driven underground. These were people who found a chamber that led down into the earth. It was warmer there, and they survived because the walls were covered in moss that gave heat and light. There were wild plants and wild animals, and the melting ice and snow leaked down into the world and formed lakes and creeks and rivers. In time these people populated all of the underground. They found gold. They discovered hissing vats of volcanic release; it’s the power source for most of what occurs here. They built this city.

“But in time, the time of Odar Rukk, the people began to return to their old ways. The ways that led to their destruction by the gods. And Odar Rukk, a scientist who helped devise the way this city works, decided, along with idealistic volunteers, that there was a need for a new and better world. Gradually, he changed these volunteers into these gold warriors, and then they captured the others and changed them. The goal was to eliminate the needs of people, and to make them machinelike.”

“All of them under his control?” I said.

“Correct,” Farr Larvis said. “Ah, here comes the voice.”

And so it came: Odar Rukk’s voice floating out from wall speakers and filling the chambers like water. It was a thin voice, but clear, and he spoke for hours and hours, explained how we were all part of a new future, that we should submit, and that soon all our needs, all our desires for greed and romance and success and war, would be behind us. We would be blended in blood and bone and spirit. We would be collectively part of the greatest race that Barsoom had ever known. And soon the gold ones would spread out far and wide, crunching all Martians beneath their steam-powered plans.

I do not know how long we waited there in the cell, but every day the gold ones came and brought us food, which was more of the gruel. They gave us water and we made our toilet where we could. And then came the day when the speakers did not speak. Odar Rukk’s voice did not drone. There was only silence, except for the moaning and crying from the captives.

“The gold ones come today,” Farr Larvis said. “On the day of Complete Silence. They take the people away and they do not come back.”

“I suggest, then, that we do not let them take us easily,” I said. “We must fight. And if they should carry us away, we should fight still.”

“If it is at all possible,” Farr Larvis said, “I will fight to the bitter end. I will fight until the machines take me apart.”

“It is all we can do,” I said. “And sometimes, that is enough.”

True to Farr Larvis’s word, they came. There were many of them, and they marched in time in single file. They brought a gold key and snicked it in the cell lock. They entered the cell, and the moans and cries of the Red Martians rose up.

“Silence,” Farr Larvis yelled. “Do not give them the satisfaction.”

But they did not go silent.

The gold ones came in with short little sticks that gave off shocks. I fought them, because I knew nothing other than to fight. They came and I knocked them down with my fist, their armor crunching beneath my Earthly strength. There were too many, however, and finally I went down beneath their shocks. My hands were bound quickly with rope in front of me, and I was lifted up.

Farr Larvis fought well, and so did his two men, but they took them, and all the others, and carried them away.

Along the narrow path between the cells we went, in their clutches, and then a curious thing happened. The half a dozen gold ones carrying me, giving me intermittent shocks with their stinging rods, veered off and took me away from the mass being driven toward the Meat Rooms, as Farr Larvis called them: the place of annihilation.

I was being separated from the others, carried toward some separate fate.

Farr Larvis called out: “Good-bye, John Carter.”

“Remember,” I said back. “We still live.”

They hauled me into a colossal room which was really a cavern. The walls sweated gooey liquid gold, thick as glowing honey. There were clear tubes running along the ceiling and they were full of the yellow liquid. In spots the tubes leaked, and the fluid dripped from the leaks and fell in splotches like golden bird droppings to the ground. The air in the room was heavily misted with gold. It gave the illusion that we were like flies struggling through amber. There was a cool wet wind flowing through the cavern, its temperature just short of being cold.

I was carried forward to where a domed building could be seen at the peak of a pyramid of steps. On the top of the dome was an immense orb made of transparent stone, and it was full of the golden elixir. It popped and bubbled and splattered against the globe. Up we went, and finally, after giving me a series of shocks to make sure my resistance was lowered, they laid me on the ground and stood around me, waited, looked up at the dome and globe.

A part of the dome’s wall lowered with the expected hiss of steam. A multi-wheeled machine rolled out, and in it sat an obese, naked, red-skinned man with a misshapen skull. The skull was bare except for a few strands of gray hair that floated above it in the gold-tinted wind, wriggling like albino roach antennae. The eyes in the skull were dark and beady and rheumy; one of them had a mind of its own, wandering first up, and then down, then left to right. His massive belly looked ready to pop, like an overripe pomegranate. He was without legs. In fact, from his lower torso on, he was machine. Hoses and wires ran from the wheeled conveyance to the back of his head, and when he breathed, steam issued from his mouth and nose like a snorting dragon. His long, skeletal fingers rested on the arms of the chair, in easy reach of a series of buttons and switches and levers and dials. Off of the chair trailed transparent tubes pulsing with the gold fluid, and red and blue and green and yellow wires. All of this twisted back behind him, along the ramp, and into the dome, and I could see where the wires and horses curled upward toward the globe. All of this ran out from the globe and into the wall behind it.

Having recovered somewhat from the electrical shocks, I slowly stood up. Two of the gold men moved toward me.

“Leave him,” said the man, who I knew to be Odar Rukk. I had heard his voice many times over the speakers in the walls. “Leave him be.”

He fixed his good eye on me. “Your name?”

I pushed out my chest and stuck out my chin. “John Carter, Warlord of Mars.”

“Ah, that obviously means something to you, but it means nothing to me. Do you know who I am?”

“A madman named Odar Rukk.”

He smiled, and the smile was a glint of metal teeth and hissing steam. “Yes, I am Odar Rukk, and I may be the only sane man on Barsoom.”

“I would not put that up for a vote,” I said.

“Oh, I don’t know. My golden army would agree.”

“They neither agree or disagree,” I said. “They blindly obey.”

“As do all armies.”

“Armies and men fight for beliefs and for purpose.”

“Oh. You titled yourself Warlord of Mars. Do you not enjoy battle? War?”

I said nothing. He had spoken the truth. It was not all about ideals.

“I brought you here because my golden warriors have been recording in their memory cells all that they saw you do. They know you single-handedly brought down my flying machine, destroyed one of their kind in the crash, another with your swordsmanship. Those events they recorded in their heads and now those events are in my head.”

Odar Rukk paused to tap his skull with the tip of his index finger.

“They brought those images to me, and with but a twist of a dial and the flick of a switch, they come into my head and I see what they have seen. They showed me a man who could do extraordinary things. Before I take those things from you, tell me, John Carter, Warlord of Mars, why are you so different?”

“I am from Earth. The gravity is heavier there. It makes me stronger here. And most importantly, I do what I do because I am who I am. John Carter, formerly of a place called Virginia.”

“You, John Carter, will be my personal fuel. I will suck out your spirit and your abilities and into me directly they will go.”

“You will still be you. Not me.”

“I do not wish to be you, John Carter. I wish to take away your spirit, your powers. I will use them to live longer yet. I will use them to change this planet for the better. Soon, I will spread our empire. I will take away the insignificant needs of men and women. I will eliminate hunger and fear and war, all the negative aspects.”

“Except for yourself,” I said. “You remain very manlike.”

Odar Rukk smiled that steamy, gleaming smile again. “Someone must rule. Someone must control. There must be one mind that oversees and does not merely respond. That is my burden.”

“What you have done here is nothing more than an exercise in vanity,” I said.

“Have it your way,” he said. “But soon your strength, your will, shall be contained inside of me, and I will be stronger than before. When I saw what you could do, your uniqueness, I decided it would be all mine. Not spread out among the others. But all mine.”

“Being unique somewhat spoils your vision of everyone and everything being alike, does it not?”

“I have no need to argue, John Carter,” he said. “I have the power here, not you. And in moments, when you are strapped in and sucked out and all those abilities are pumped into me, you will cease to exist, and I will be stronger.”

The shocks had worn off, and the ropes they had tied me with had loosened. They had not been tied that well to begin with, but still, they were sufficient to hold me. No matter. I had decided I would give my life dearly before I let this monster take away my spirit, my abilities, my blood and bones and flesh.

And then, when I was on the verge of hurling myself at Odar Rukk, knocking him out of his chair with my body, with the intent of trying to bite his throat out, there was an unexpected change of situation.

* * *

There was a noise beyond our cavern, a noise that echoed into our huge chamber and clamored about the walls like a series of great metal butterflies clanging against the walls. It was the sound of conflict from beyond our cavern. Somehow, I knew it was Farr Larvis and his two warriors. They were managing to put up a last hard fight.

In that moment, with Odar Rukk’s head twisting about, trying to find the source of the sound, the gold ones having turned their attention to the back of the cave, I jumped toward the nearest gold one, grabbed his sword with my bound hands, and pulled it from its sheath. I sliced at him, catching him beneath the helmet and slicing his head off his shoulders. There was a spurt of gold liquid from his neck, a spark from a batch of severed wires, and he went down.

I managed to twist the sword in my hand and cut my rope and free my hands. Then I turned as they came at me. I wove my sword like a tapestry of steel. Poking through eye slots, slicing under the helmets, taking off heads, chopping legs and arms free at joint connections where the armor was thinnest.

I spun about for a look, saw Odar Rukk had wheeled his machine about and was darting up the ramp, back into the dome. Already the ramp was rising. Soon he would be safe inside. I leapt. My Earthly muscles saved me again, for the horde of gold men were about to be on me, thick as a cluster of grapes, and even with all my skill, I could not have fought them all. I landed on the ramp. It was continuing to lift, and it unsettled my footing. I started to slide after Odar Rukk, who had already driven himself inside the dome.

When the door clamped shut, I was in a large room with Odar Rukk. He had turned himself about in the chair, the hoses and wires fastened to the back of it twisted with him. I saw at a glance that the walls were lined with darkened bodies, both Red folk and Green Men. They hung like flies in webs, but the webs were wires and hoses and metal clamps. This was undoubtedly Odar Rukk’s power source, something he had planned for me to become a part of.

“This is your day of reckoning, Odar Rukk,” I said.

From somewhere he produced a pistol and fired. The handguns of Barsoom are notoriously inaccurate, as well as few and far between, but the shot had been a close one. I leapt away. The gun blasted again, and its beam came closer still. I threw my sword and had the satisfaction of seeing it go deep into his shoulder. His gun hand wavered.

Leaping again, I drove both my feet in front of me. I hit Odar Rukk in the chest with tremendous impact. The blow knocked him and his attached machine chair backward, tipping it over. Odar Rukk skidded across the floor. The part of him that was machine threw up sparks. Hoses came unclamped, spewed gold fluid. Wires came loose and popped with electric current. Odar Rukk screamed.

I hustled to my feet and sprang toward him to administer a death blow, but it was unnecessary. The hoses and wires had been his arteries, his life force, and now they were undone. Odar Rukk’s body came free of the chair connection with a snick, and he slipped from it, revealing the bottom of his torso, a scarred and cauterized mess with wire and hose connections, now severed. The fat belly burst open and revealed not only blood and organs, but gears and wheels and tangles of wires and hoses. His flesh went dark and fell from his skull and his eyes sank in his head like fishing sinkers. A moment later, he was nothing more than a piece of fragmented machine and rotten flesh and yellow bones.

I recovered his firearm, cut some of the wire from the machine-man loose with my sword, used it to make a belt, and stuck the pistol between it and my flesh. I recovered my sword.

Outside of the locked dome, I could hear the clatter of battle. Farr Tharvis had been more successful than I expected. But even if he had put together an army, the metal men would soon make short work of them.

I looked up at the pulsing globe that rose through the top of the dome. I jumped and grabbed the side of the dome, in a place where my hands could best take purchase, and clambered up rapidly to the globe, my sword in my teeth.

Finally I came to the rim below the globe. There was a metal rim there, and it was wide enough for me to stand on it. I took hold of my sword, and with all my strength, I struck.

The blow was hard, but the structure, which I was now certain was some form of transparent stone, withstood it. I withdrew the pistol and fired. The blast needled a hole in the dome and a spurt of gold liquid nearly hit me in the face. I moved to the side and it gushed out at a tremendous rate. I fired again. Another hole appeared and more of the gold goo leapt free. The globe cracked slightly, then terrifically, generating a web of cracks throughout. Then it exploded and the fluid blew out of it like a massive ocean wave. It washed me away, slamming me into the far wall. I went under, losing the pistol and sword. I tried my best to swim. Something, perhaps a fragment of the globe, struck my head and I went out.

When I awoke, I was outside the dome, which had collapsed like wet paper. I was lying on my back, my head being lifted up by a smiling Farr Larvis.

“When you broke the globe, it caused the gold men to collapse. It was their life source.”

“And Odar Rukk’s,” I said.

“It was a good thing,” Farr Larvis said. “The revolt I led was not doing too well. It was exactly at the right moment, John Carter. Though we were nearly all washed away. Including you.”

I grinned at him. “We still live.”

There isn’t much left to tell.

Simply put, all of us who had survived gathered up weapons and started out as the machinery that Odar Rukk had invented gradually ceased to work. The drawbridge was down. All the gates throughout the underground city had sprung open, and had hissed out the last of their steam. The gold ones were lying about like uneven pavement stones.

We found water containers and filled them. We tore moss from the walls and used it for light, made our way up the long path out. After much time, we came to the surface. We gathered up fruit and such things as we thought we could eat on our journey, and then we climbed higher out of the green valley until we stood happily on the warm desert sand.

It was a long trip home, and there were minor adventures, but nothing worth mentioning. Eventually we came within sight of Helium, and I paused and stood before the group, which was of significant size, and swore allegiance to them as Jeddak of Helium, and in return they swore the same to me.

Then we started the last leg of our journey, and as we went, I thought of Dejah Thoris, and how so very soon she would be in my arms again.

Check out this process post behind Gregory Manchess’ painting of John Carter and the flying metal dragon.

You can find excerpts and more from the forthcoming Under The Moons of Mars John Carter anthology by visiting its promotional site.

“The Metal Men of Mars” © copyright 2011 Joe R. Lansdale

Illustration © copyright 2011 Gregory Manchess

Good story, very much in the original style of the Mars stories.

The one new element was when John Carter exhibited symptoms of a concussion after being knocked out, which rarely happened in the old stories, where characters seemed to be knocked out every time the author wanted to move to a new chapter, and shook the effects off almost as soon as they woke up.

For me, it also evoked Doctor Who. I couldn’t help thinking of the Cybermen when the golden warriors were described, and comparing Odar Rukk to Davros, creator of the Daleks.

Enjoyed ‘The Metal Men of Mars’.

Currently reading the Barsoom series, this time in order. I shall consider adding ‘Under the Moons of Mars: New Adventures on Barsoom’ to my collection. I see it will be available for Kindle. Good. Availability on Kindle makes it a near certainty that I will buy the book.